A woman with her baby niece at the The United Court of Nineveh in Qaraqosh. Aside from the trials of former IS fighters, weekdays from Sunday to Thursday, around 300 people gather in front of the doors of the court. These individuals, who arrive at the same time as the IS fighters, are the victims of the three-year IS rule who seek justice.

Refugees from West Mosul, being received by the Iraqi army and NGOs. The third phase of the military operations to liberate the city from the terrorist organization ISIS started in February 2017 and most of the combats between ISIS militants and the Iraqi armed forces will take place in populated areas.

ICRC's Director of Operations Dominik Stillhart visiting IDP camps in the region around Mosul. As Iraqi families continues to stream out of the city of Mosul as a result of the Iraqi army offensive to retake the city from the so called Islamic State, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is providing aid to IDPs arriving in the camps. IDPs from Mosul at the Debaga Camp.

The Al-Hashd Al-Sha'abi, or People's Mobilization Forces (PMF), also known as the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) ) is an Iraqi state-sponsored umbrella organization composed of some 40 militias, which are mainly Shia Muslim groups, but there are Sunni Muslim, Christian, and Yazidi individuals as well. The People's Mobilization was formed for deployment against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). In this picture: Children passing by the decomposing dead Islamic State militant.

As the battle continues for the liberation of the remainder of Mosul from the Islamic State (IS), forces answering to the Interior Ministry have been playing more of a central role than those under the Defense Ministry. Casualties are rising among the federal police, however, and several members were reportedly captured by IS after they ran out of ammunition March 20. A ministry official told Al-Monitor that the men had been killed, but denied that they had been captured prior to their death

General Amir Shakir heading the Iraqi Federal Police forces against the Islamic State in West Mosul and other high rank officers meeting with their soldiers during the Ramadan celebration in West Mosul. The high rank officers met all all at the same time at Mosul's frontline as a defiance gesture against ISIS.

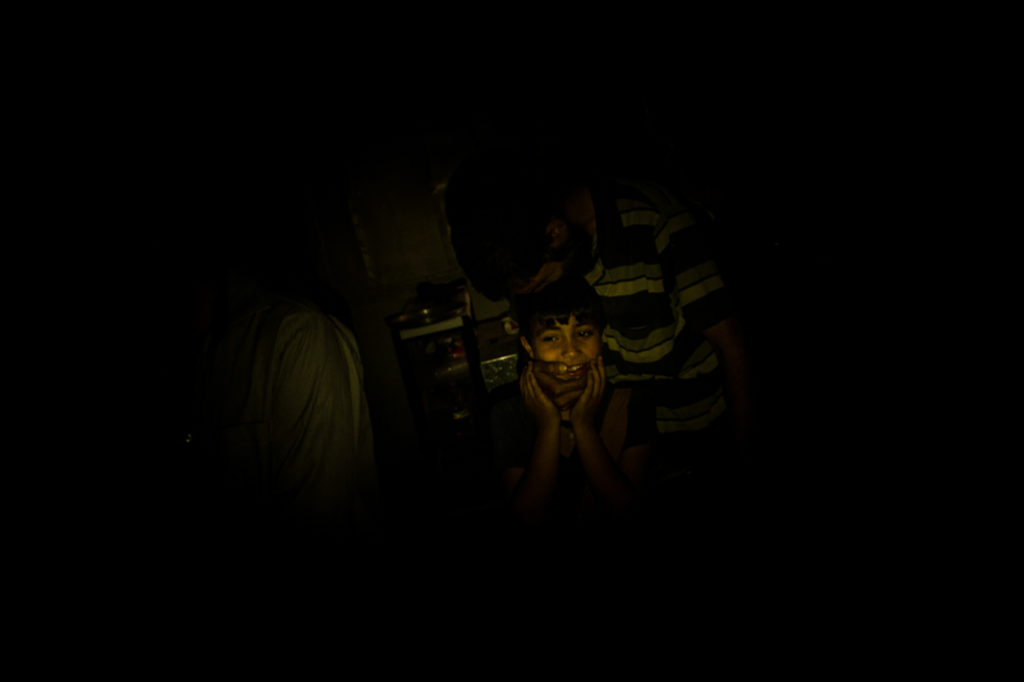

The Al-Hashd Al-Sha'abi, or People's Mobilization Forces (PMF), also known as the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) ) is an Iraqi state-sponsored umbrella organization composed of some 40 militias, which are mainly Shia Muslim groups, but there are Sunni Muslim, Christian, and Yazidi individuals as well. The People's Mobilization was formed for deployment against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). In this picture: A boy observing new arrivals at the Qayarah IDP camp. Thousands of civilians have been displaced by the fights against the Islamic State

Two men carrying a disabled man while fleeing the western Mosul neighbourhood of Hay Tayaran. In March 2017, the Iraqi Federal Police declared full control over this strategic district opening the doors for the full military operation to retake the city from the Islamic State organisation. The battles gave civilians held in this neighbourhood the chance to leave the city seeking protection in other previously liberated areas. Humanitarian organisations have accused ISIS militants to deliberately shoot at fleeing residents.

The Al-Zahra hospital in Mosul, has been receiving patients from all the neighborhoods in the east side of Aleppo since November 2016 when the Iraq special forces, took control over the region from Islamic State Militants. The hospital functioned as a community clinic before the offensive against the Islamic State that started in August 2016 but now, doctors working in the clinic have to perform several kinds of treatments and surgeries that they are not materially prepared for. In this picture: Four years old Emad is being treated by a doctor. Thirteen years old Mahmood came back to the hospital for a follow up after a orthopedic surgery after he had both his legs injured when he was run by a car.

The Al-Hashd Al-Sha'abi, or People's Mobilization Forces (PMF), also known as the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) ) is an Iraqi state-sponsored umbrella organization composed of some 40 militias, which are mainly Shia Muslim groups, but there are Sunni Muslim, Christian, and Yazidi individuals as well. The People's Mobilization was formed for deployment against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). In this picture: Fighters from Al-Hashd Al-Sha'abi driving in the desert towards the Tal Afar frontline.

Soldiers from the Iraqi Federal Police rescuing the body of an elderly women killed in the streets of Old Mosul while she tried to scape the clashes between the Iraqi Government Forces and ISIS Militants. Since the start of the battles to liberate the city, humanitarian agencies and human rights organizations as HRW accused the so called Islamic State of “indiscriminately’ attacking people who refused to retreat from the Iraqi city of Mosul alongside jihadists.

The Al-Hashd Al-Sha'abi, or People's Mobilization Forces (PMF), also known as the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) ) is an Iraqi state-sponsored umbrella organization composed of some 40 militias, which are mainly Shia Muslim groups, but there are Sunni Muslim, Christian, and Yazidi individuals as well. The People's Mobilization was formed for deployment against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). In this picture: Al-Hashd Al-Sha'abi fighters commemorating their victory over Islamic state Militants.

The Salam hospital in Mosul, was the major hospital in the city and has been destroyed beyond recognition by coalition airstrikes and ground fights between Iraq troops and Islamic State Militants. The damages caused by some of the worst fights seen so far in Mosul compromised the entire structure and several floors have been completely destroyed by airstrikes. The airstrikes took place on December 8th 2016 after the Iraqi army asked for air support to attack ISIS militants using the hospital compound as a base for their operations. American air Force Col. John L. Dorrian, the spokesman for Operation Inherent Resolve, told reporters that the coalition did not "have any reason to believe civilians were harmed." However, when specifically asked whether there were patients at the city's main hospital, Dorrian said that was "very difficult to ascertain with full and total fidelity." A review of the intelligence that led to the decision is underway, he said. In this picture:

Soldiers from the Iraqi Federal Police after entering an ISIS command center in the West side of Mosul during the second phase to retake the city. In June 2014, after taking control of the city of Mosul, ISIS fighters came as close as 25 km to enter the Iraqi Capital Baghdad. Two and a half years later, it is now Isis fighters who have to fight street-to-street to hold their last remaining neighbourhoods in west Mosul. Despite the undeniable fact that the Iraqi forces are winning the war, the often premature and sometimes untrue statements from Iraqi officials, eager to announce their advances and victories, hide the high prices paid in civilian and military lives lost during the battles.

After the liberation of the east side of Mosul, ISIS suspects have been executed with their bodies exposed in public in revenge of the crimes committed by the group during the 2 years they controlled the city. In this picture. The bodies of two men showing signs of torture and execution found a the Salam Neighborhood in Mosul.

Mosul, Iraq. December 2016 – July 2017

– Are not you afraid of me? Don’t you feel scared of me?

– No, I know you wouldn’t attack me without an order to do so.

– No, I would never do that.

– But would you like to receive that order?

– Of course!

Unlike anything or anyone else there, the Sun didn’t need superior orders to be violent. The beating heat was already over fifty degrees. Unrefreshing, the hot wind of that morning in Mosul flowed through our nostrils mingled with dust and the nauseating, oily stench of the countless bodies that rotted everywhere.

Beside us, the body of a man, thrown face down on the ashes of the burned vegetation, still let fresh blood flow through its various wounds. Haider and his soldiers had executed him seconds earlier.

We were under the oldest bridge in Mosul destroyed months before by western and Iraqi air strikes that isolated the eastern and western parts of the city. There, the Iraqi federal police had mounted what they called a “trap” against Islamic state fighters trying to flee swimming across the Tigers.

Haider, a 32-year-old first lieutenant from Baghdad, once, a student of English literature and law, was responsible for activating the trap every time a prey, exhausted or wounded, being carried by the current, tried to find refuge among the bridge wreckage that squirmed through that part of the river.

Despite his serious face, his expression of terror and fatigue, when he was captured by the soldiers of the first battalion of the federal police, on leaving the river, the man lying dead a few meters from our feet appeared to be in good physical condition. Unlike the thousands of civilians who had left that same part of the city, skeletal and diseased, his body were well nourished, his arms were strong, and his shoulders were wide like those who exercises specifically for this.

His hair was short and his beard long enough for a soldier to pull him out of the water grabbing him by it. He wore dark trousers that came down just below his knees and wore a white T-shirt with the word “Florida” stamped above the design of a landscape very different from the one in which he was at that moment.

He desperately tried to communicate with the soldiers who beat him, shouting and filming the whole situation with their cell phones. He said repeatedly that he was not a combatant; “Ana last Daesh, Ana last Daesh Saidi!

His strength and his hopes of survival lasted only the few meters and minutes that the Iraqi soldiers needed to drag him as they stripped him of his clothes violently.

Without enduring the pain and humiliation of the punches and threats he received, in total dismay, the man allowed his body to fall without any resistance on the ground to be immediately executed with several shots of rifles and pistols.

Happy and joyful, Haider started walking towards the shade, smiling alongside his soldiers as they compared the videos of the murder they had just committed.

A media blackout imposed by the Iraqi army had severely restricted journalist access. But the months I had spent embedded with the Federal Police on the Mosul frontlines and the confidence these soldiers had in me enabled me to be present. However, witnessing the aftermath of the final stages of the battle was still not without risk of arrest and I was eventually forced to leave under the threat of gunfire.

July 17 marked exactly one week since the Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi had been in Mosul to officially declare victory over the terrorist group that controlled the city for 3 years and threatened to invade the capital Baghdad but the need for a “trap” to eliminate Islamic State fighters yet active in the city made it clear that the declaration of victory, if not premature, had been made to serve something else but the truth.

A few hundred meters upstream, Iraqi special forces soldiers were still fighting the last Islamic State militants, and their rifle shots were only muffled by the arrival of an army helicopter that, with very low flights and sharp dips, fired missiles and blasts of machine gun against a certain point also on the banks of the Tigers.

The air raids lasted less than an hour, in a video posted on social media by the army, a camera installed in the helicopter, showed how the few survivors were killed while they tried in vain to hide from the bullets and explosions.

Euphoric with the eminence of a definitive victory, soldiers from all battalions began to celebrate as they watched what appeared to be a show of aerial acrobatics just a few feet from their eyes.

A cloud of fine dust rose, irritating everyone’s eyes and nostrils even more. A young soldier wearing an Iraqi flag like a superhero cloak and two other comrades climbed enthusiastically the ruins of the destroyed buildings to reach the newly, and final conquered spot. Arms, legs, heads, hundreds of whole or shattered bodies, decomposing for a short and for a long time, being eaten by crawling and flying insects were scattered all over the place, over and under a huge pile of debris. The scene where the last fighters of the Islamic state and their families were killed could only be compared to a hell.

Soldiers hurriedly tossed all the rubble around looking for weapons and documents, not caring that their steps were almost all over the bodies of the terrorists, but also over the bodies of women and children.

Less than two meters from touching the waters of the Tigers, a baby’s filthy body wearing only a camouflaged T-shirt was still tossed under pieces of metal and barbed wire. His birth and death had just happened.

Beneath his feet, a colour portrait of a young man who did not appear to be Iraqi. A body of a woman dried by the frying sun stretched out from the debris in a crucifix shape and the mutilated bodies of at least four other older children were squeezed just steps away. Were they his father, his mother, and his brothers and sisters?

As if they had set a meeting to go hand in hand, the gestation of that child and the military offensives that defeated the Islamic State in Mosul had begun exactly 9 months ago, now, those who were born today and those who are still alive, will have to live with the consequences of the crimes committed for the fetus of peace to try to exist in Iraq one day.