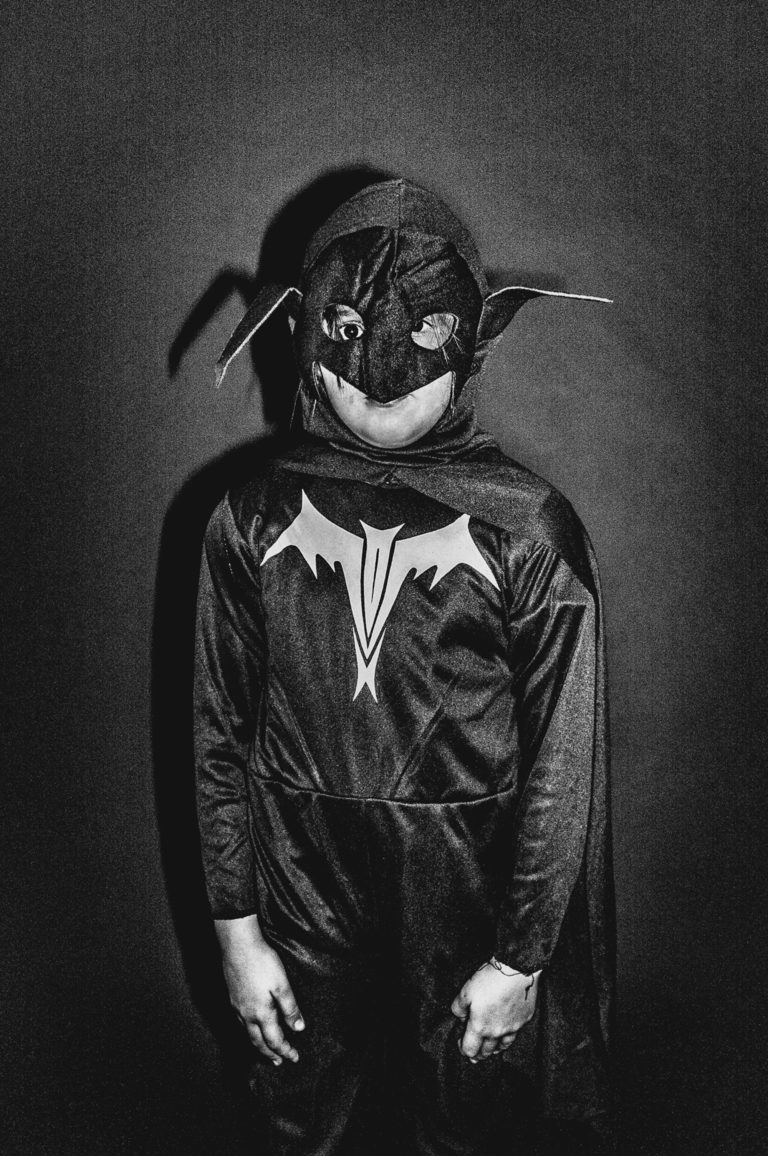

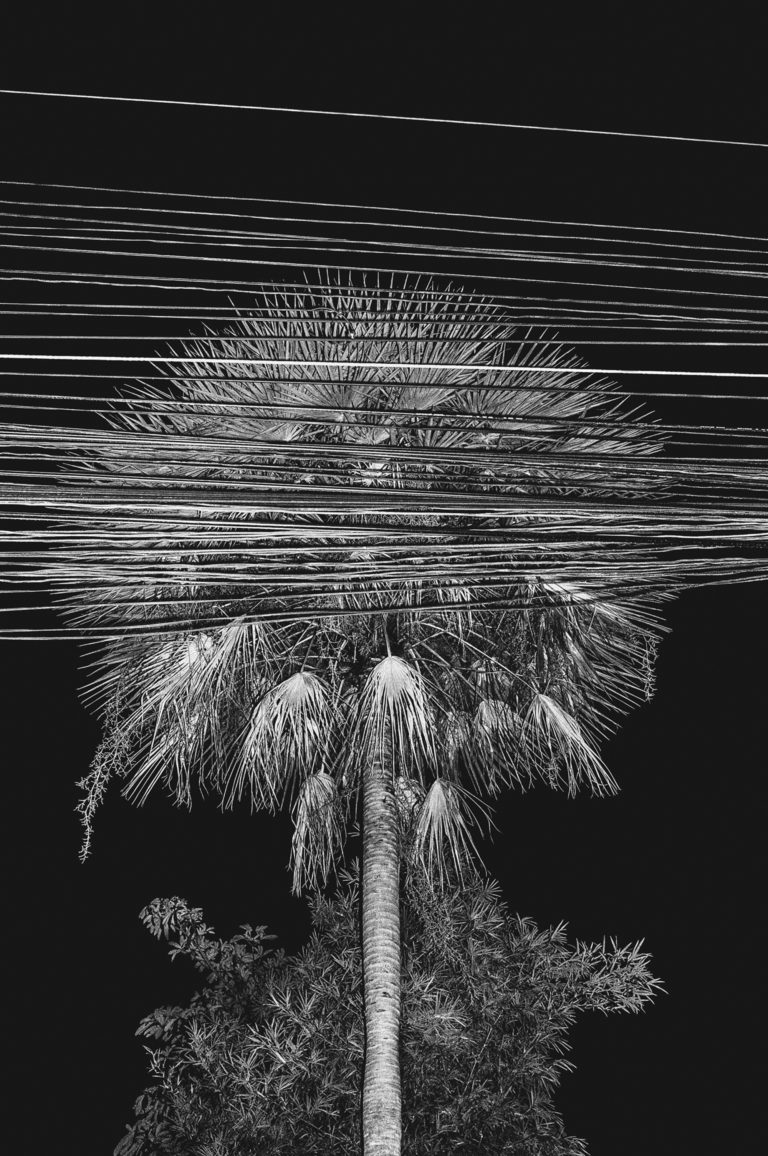

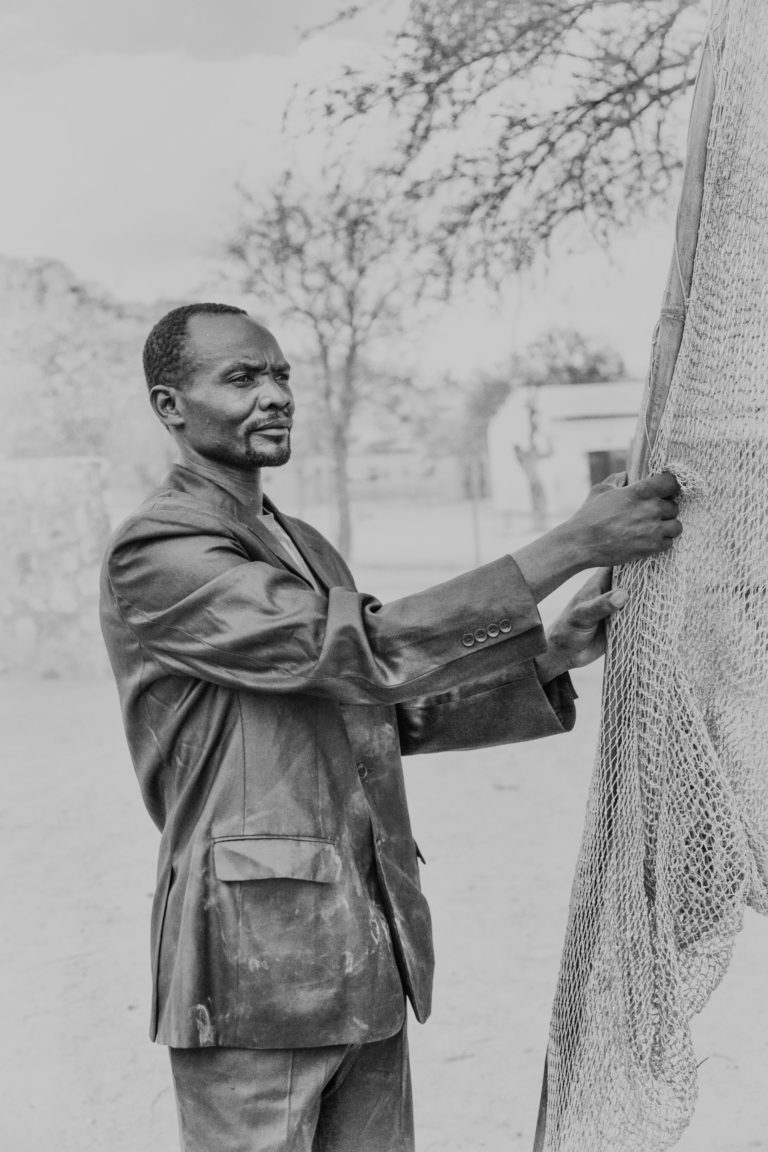

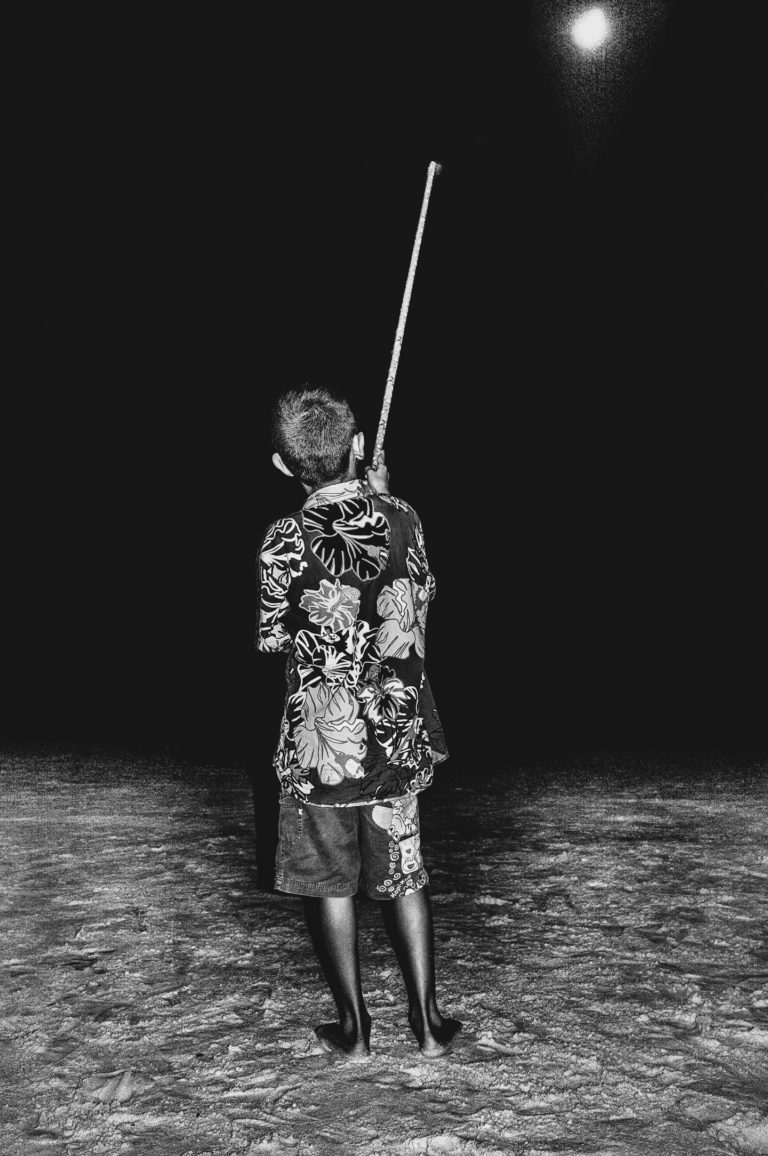

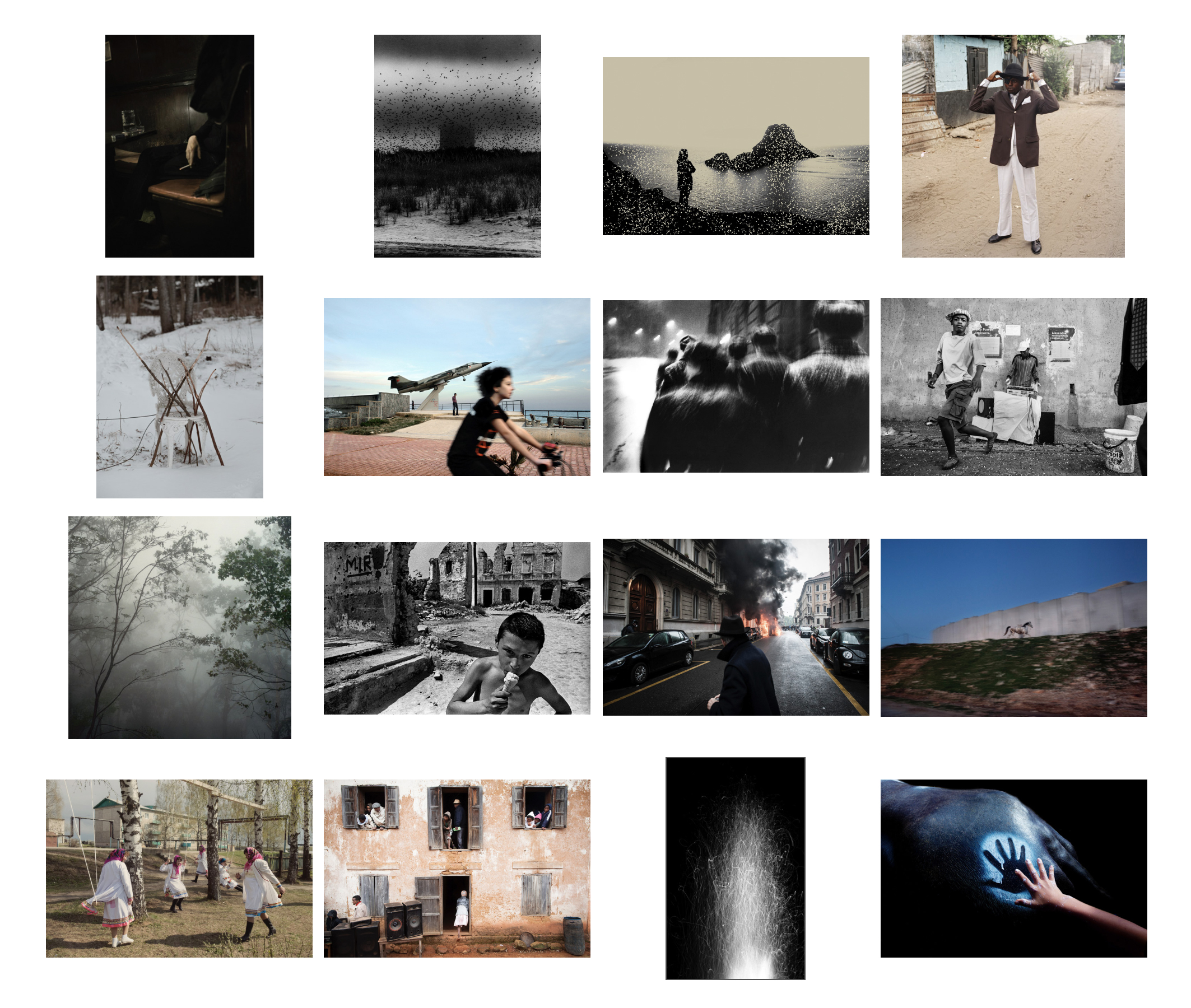

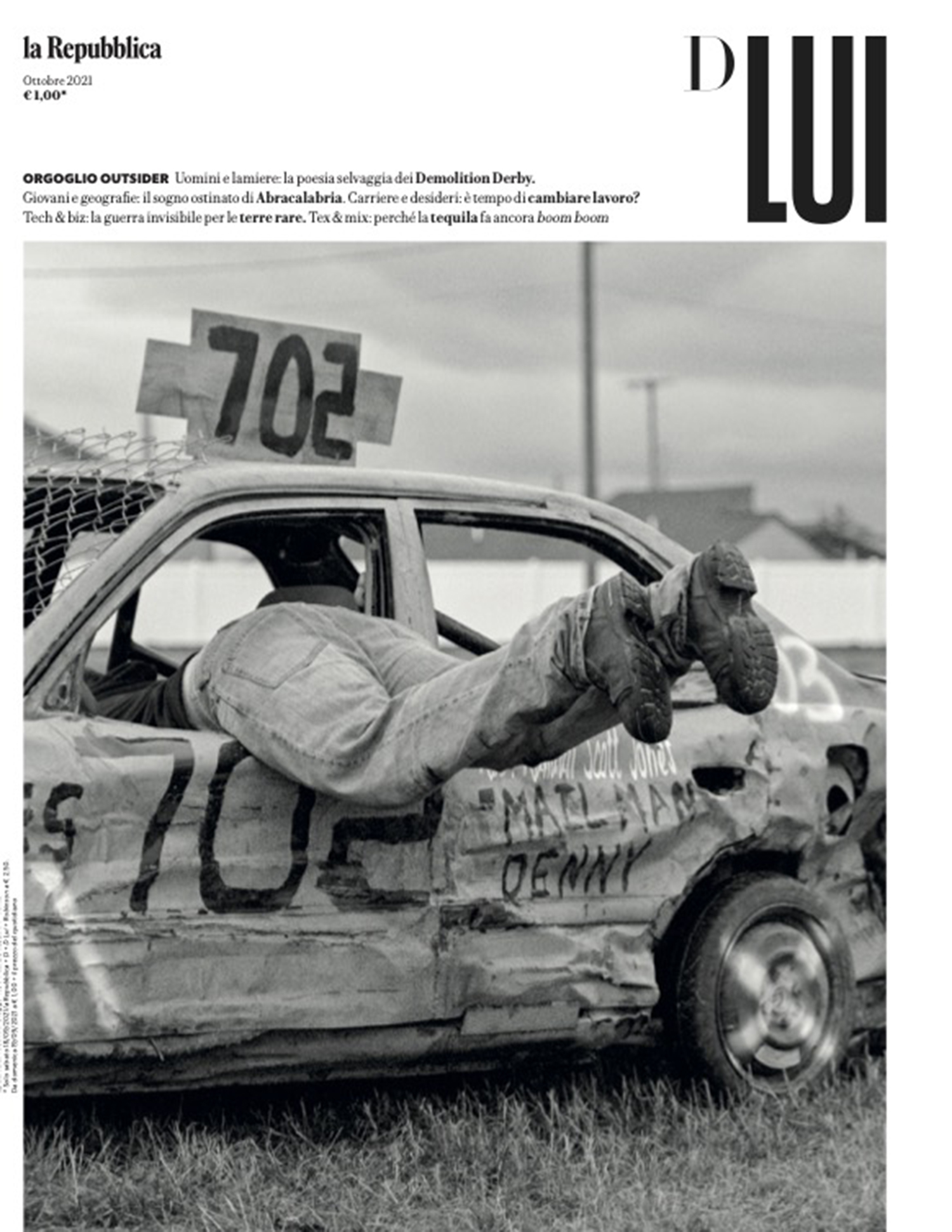

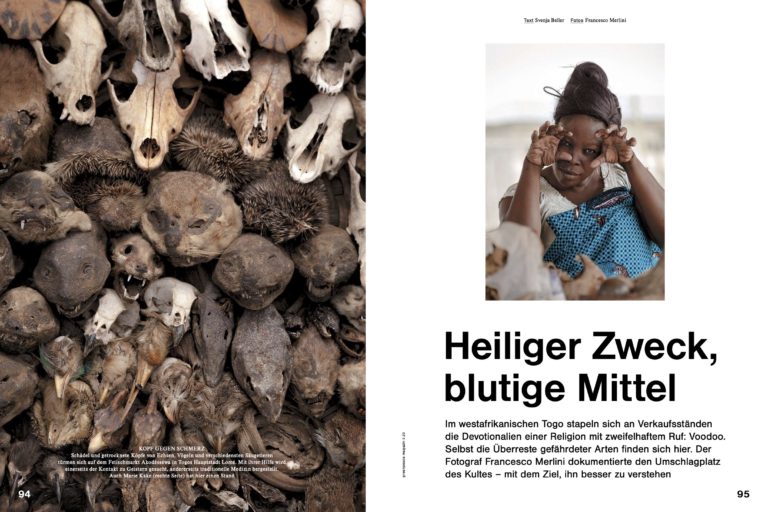

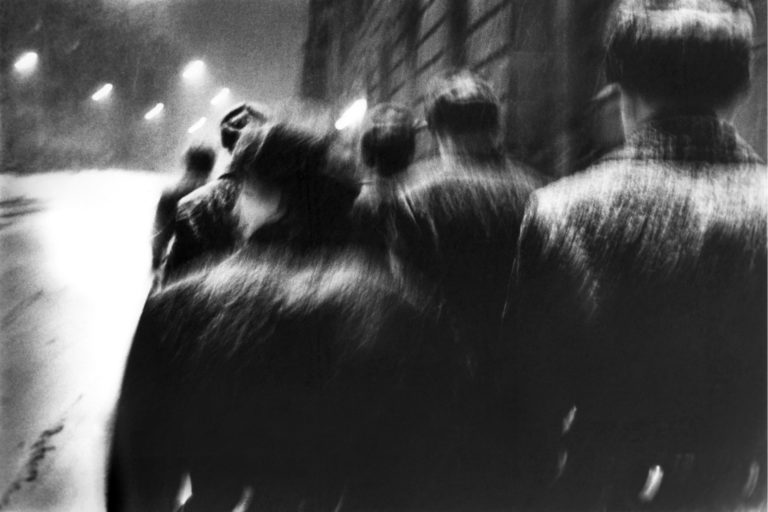

Sometimes I feel like many photographers, including me, have perhaps stopped looking for what, for better or for worse, is extraordinary and unrepeatable in our world.

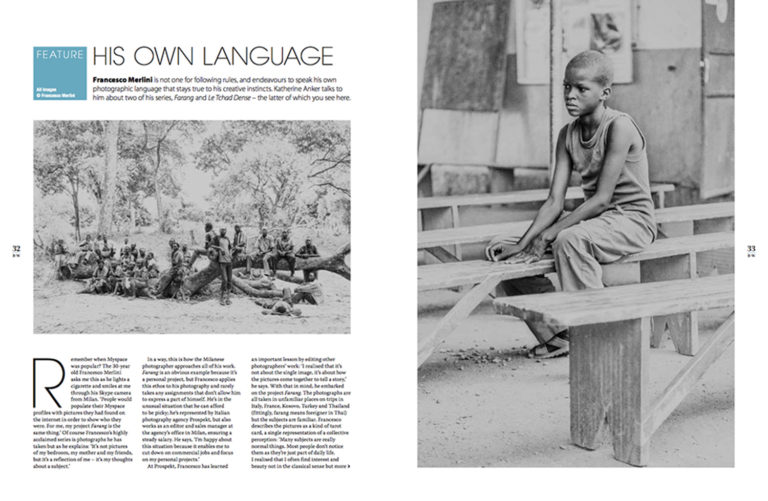

In contemporary photography, after some successful experiments by the great masters, the gaze has increasingly turned to the inanimate and everyday panorama, struggling for a “modern” photographic language and claiming the extraordinary nature of the mediocre to hide a rampant rashness, superficiality and laziness. All this created a fertile ground for an arid formalism made up of headlights, fruit, hands and pipes.

Still lifes for docile eyes.